In her book Sorry States, Jennifer Lind extolls the reconciliatory and “healing” benefits of states apologizing for past human rights abuses. She points to the contrasting events in post-World War II Japan and Germany, wherein Japan refused to apologize while Germany openly acknowledged its crimes.

Japanese prime ministers (PM) across the decades have expressed regret for the pain and suffering caused to the people of Burma, Australia, South Korea, and China. Incumbent PM Shinzo Abe, too, contends that Japan has “repeatedly apologized” for its past actions. However, regret does not amount to an apology. Moreover, textbooks used in Japanese schools curiously omit critical events from the Nanjing Massacre of 1937, during which the Japanese military raped and mutilated more than 400,000 Chinese girls and women and killed anywhere between 50,000 and 300,000 people. They further claim that the 1941 Pearl Harbor attack was a legitimate response to a US embargo, which Japan sees as a “form of undeclared war”. It is perhaps for this reason that only 1% of South Koreans and 4% of Chinese people feel that Japan has “sufficiently apologized for its military actions”.

Germany, on the other hand, has made numerous apologies to atone for the crimes of the Nazis. It has repeatedly asked for “forgiveness” and acknowledged its “responsibility” in leaving a “painful legacy”. In 1970, when West German Chancellor Willy Brandt visited a memorial for the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, he dropped to his knees in apology. In 1985, President Richard von Weizsaecker said anyone who denied Nazi atrocities was “blind”. Similarly, the current Chancellor, Angela Merkel, expressed gratitude for the “hand of reconciliation that was extended” to Germany in spite of the “suffering” that her country wrought upon the world. In Germany, Nazi symbols are only allowed to be displayed for educational purposes, public Nazi imagery has been destroyed, and all Nazi symbols have been erased from Nazi-era buildings. Simultaneously, denial of the Holocaust is a criminal act, in contrast to Japan, which often papers over its crimes or places the blame for its actions on Western actors. There are no monuments or statues honoring Nazi leaders, and Germany has also buried Nazi officials in mass, unmarked graves to avoid their “resting grounds” becoming “shrines”. This is in stark contrast to Japan, where the Yasukuni Shrine commemorates 1,068 convicted war criminals and is frequently visited by Japanese leaders.

Germany’s ability and willingness to extend not just remorse but apologies for its actions has allowed for the wounds of its own people and the countries it harmed to heal, facilitating a new era of friendship and cooperation. Conversely, Japan, which continues to hold on to relics of the past, still has strained relations with South Korea and China, and to a lesser extent with Malaysia, the Philippines, Indonesia, and Australia. Only 57% of Japanese people feel that their country has sufficiently apologized for their actions, in comparison to 73% of Germans. Similarly, while only 46% of Japanese people think relations with neighboring countries are somewhat or very good, this figure rises to 94% in Germany. Likewise, 50% of Japanese people think relations with neighboring countries are somewhat or very bad, compared to just 4% of Germans who think the same about their country.

Ultimately, one’s ability and willingness to apologize is derived from a concurrent ability and willingness to feel shame. Simultaneously, a society’s inclination to apologize is derived from its politicians’ ability and willingness to instill a self-critical and reflective political culture. As one turns away from Germany and Japan and casts their eyes towards India, one wonders whether Indians will look back at this period in Indian history and politics with shame. While one must concede that the scale of events is simply not comparable to that of Nazi Germany or Japanese imperialism, there are nonetheless strong undercurrents of systemic discrimination and oppression. Moreover, setting the threshold for an apology at imperialism or a Holocaust-level event excuses the vast majority of transgressions committed by governments. India is currently mired in an era that is plagued by communal violence, blind and unquestioning allegiance to discriminatory new laws, attempts to rewrite history, and eroding freedom of speech and the press. Moreover, this seemingly cataclysmic shift is driven in part by political leaders who seek to divide citizens along religious lines at every turn, rather than celebrate India’s rich and diverse tapestry.

In September 2017, journalist Gauri Lankesh, a staunch critic of Hindutva politics, was shot dead outside her home by three unidentified assailants for criticizing the BJP-led Karnataka government.

In February 2018, an eight-year-old girl from a Muslim family was raped and murdered by eight Hindu men. Yet, hand in hand with several lawyers and members of the Hindu public, the right-wing Hindu Ekta Manch, along with two former and one current BJP minister, demanded the release of a special police officer (SPO), one of the eight accused.

In June 2019, a Muslim man was “tied to a pole and severely beaten” while being forced to chant “Jai Shri Ram” (Hail Lord Ram) by an angry mob who alleged that he was a thief. He died in hospital from his injuries.

Furthermore, a Human Rights Watch report reveals that, with support from law enforcement and Hindu nationalist politicians, radical cow protection groups have injured 280 people, and killed at least 44, in over 100 attacks between May 2015 and December 2018. From the 44 killed, 36 were Muslim. Yet, these same gau rakshaks are complicit in India’s open garbage system that threatens the health and safety of cows. Consequently, it can be argued that cow vigilantism has more to do with religious differences than it does with protecting cows.

Also Read: Are Cows Sacred In Name Only?

These bone-chilling events are hardly isolated incidents, either. In fact, the India Spend Initiative found that roughly 90% of religiously-motivated hate crimes in the country since 2009 have taken place after the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) came to power in 2014. This relationship cannot be haphazardly dismissed as correlational when BJP Members of Legislative Assembly (MLAs) openly threaten Muslim vegetable sellers or tell constituents not to buy produce from them, or when Hindu lynch mobs boldly proclaim that the “police is on our side because of the government”.

India now ranks 142nd out of 180 countries in the Reporters Without Borders’ 2019 World Press Freedom Index, down from 133rd in 2016. There have been 357 internet shutdowns in India since 2014, far more than any other country. In fact, in the northern Indian state of Kashmir, the government imposed the longest-ever internet-shutdown in a democratic nation, yielding disastrous economic and health outcomes. It is for these reasons that India dropped from 27th to 51st on the Economist Intelligence Unit’s (EIU) Democracy Index between 2014 and 2020.

Also Read: Does India's Healthcare Industry Need to Become Less Internet-Reliant Under the BJP?

This erosion of democracy and slide into chaos has precipitated events like the closely-linked JNU and CAA/NRC protests, and the recent Delhi riots, which were marred by police brutality, but also by disinformation campaigns from both sides that preyed on and magnified growing fractures in Indian society. Puppeteering these events are politicians, who openly rally supporters to “shoot” the “traitors of the country”.

It can be reasonably argued that these politicians and their supporters know that they are taking morally questionable actions, to say the very least, and that they choose to do so anyway. The driving factor behind such behavior is the complicity of the state, which gives perpetrators less fear of repercussion for their actions; however, it is also guided by the Hindutva right’s unflinching commitment to shaping the country in its image, through whatever means necessary. At such a juncture, it becomes crucial to ask whether the Hindutva right genuinely believe they are doing the right thing, or whether they are simply doing what they want to. While these two things are often inseparable, BJP leader Kapil Mishra’s words may suggest otherwise. In February, clashes between pro and anti-CAA protestors were escalating in Delhi, and coincided with US President Donald Trump’s visit to India. During Trump’s visit, Mishra threatened, “Till the US President is in India, we are leaving the area peacefully. After that, we won’t listen to you (police) if the roads are not vacated.” Mishra’s words were an open admission that politicians would override the decisions of the police if the ruling party’s demands of stifling dissent were not met, but also an unmistakable commitment to illegitimate and disproportionate reaction to political dissent. What other reason would he have to hide such actions from Trump, if he didn’t think it would harm India’s international image? Mishra and his ilk are fully aware of their barbarity, but are only willing to take a step back when the risks are too high, not because they feel shameful about their actions.

In fact, this inability or unwillingness to feel shame is particularly palpable in post-Independence India, wherein various governments and parties, both at the national and the state level, and common citizens across religious lines continue to harbor the underlying feelings of hatred that fuelled the seminal events in India’s post-Independence history, such as the anti-Sikh riots in 1984, the Godhra train burning incident and the ensuing Gujarat riots in 2002, and the forced exodus of Kashmiri Pandits. Thus, rather than asking whether India will look back on this era in its history with shame, it may be more pertinent to ask whether that is even possible in this country.

Also Read: Is Suppression of Political Dissent in Democracies a Right-Wing Phenomenon?

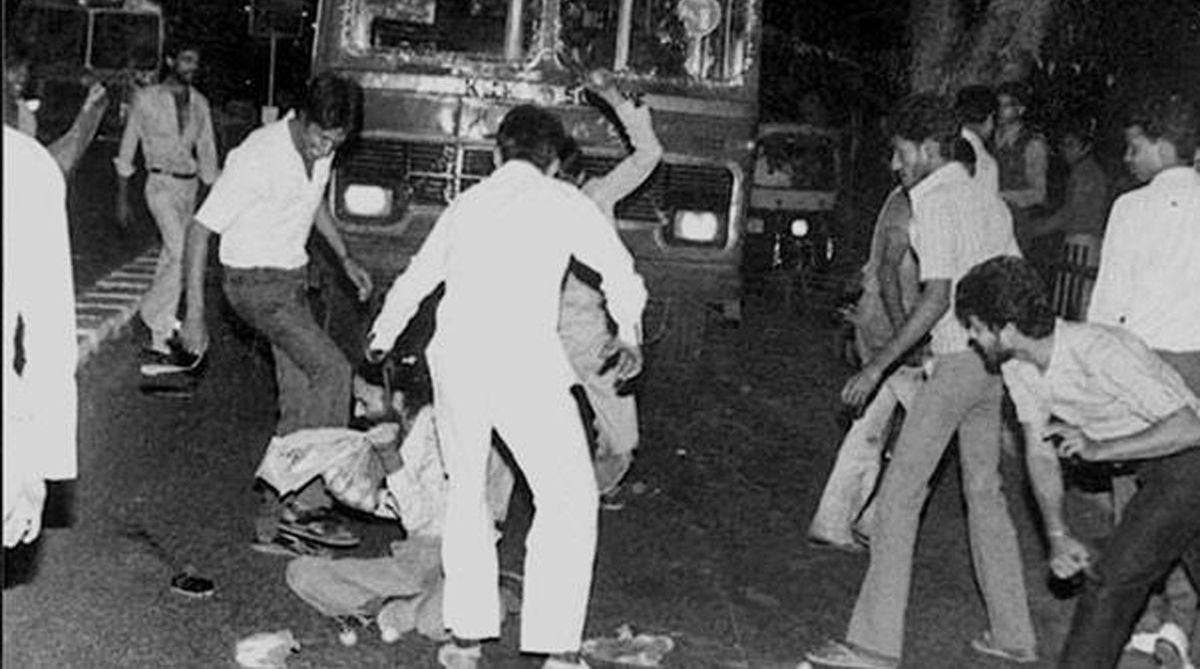

In 1984, following the assassination of PM Indira Gandhi by her two Sikh bodyguards, various regions of India descended into chaos, resulting in the deaths of 3,350 Sikhs by government estimates, or between 8,000 and 17,000 according to independent sources. The attacks were characterized by various human rights abuses, such as mass murder, rape, arson, looting, acid attacks, and immolation. It is argued that a great deal of the violence was orchestrated by the ruling Congress party, whose officials provided rioters with “voter lists, school registration forms, and ration lists” to easily identify Sikh homes and businesses. There are also allegations that senior leaders within the party doled out weapons and money to encourage and incite further violence.

Since the riots took place, over 400 rioters in Delhi have been convicted–49 were handed a life sentence, and three were imprisoned for more than ten years–but politicians have largely escaped punishment. However, while some Congress politicians, like Sajjan Kumar, have been convicted for inciting hatred and violence, others, like Kamal Nath, continue to serve in positions of power. Moreover, party leadership continues to absolve itself of responsibility or proffer any sort of meaningful apology for its role in this indelible blot on Indian history. Admittedly, former PM Manmohan Singh did make a public apology during his time in office, ‘bowing’ his “head in shame” “on behalf of our government, on behalf of the entire people of this country”. But, while this apology was much-appreciated, it was unsurprisingly rejected, as it did not come from the Gandhi family and other complicit Congress politicians.

Sonia Gandhi, the current President of the Congress Party and the wife of Rajiv Gandhi, the newly-appointed PM at the time of the riots, merely said that she could “understand” the pain of the Sikh community and expressed “regret”. However, when she was pressed for an apology, she went on to say that there is “no use recalling what we have collectively lost”. Her son, Rahul Gandhi–a member of Parliament, and the President of the party from December 2017 to July 2019–has said, “The Prime Minister of the UPA has apologised and the President of the Congress party [has] expressed regrets. I share their sentiments completely.” Additionally, he falsely claimed that the government did “everything it could do to stop the riots”. Moreover, he also distanced himself from any responsibility as the leader or a member of the party he represents, repeatedly saying that he “wasn’t involved in the riots”, “wasn’t […] a part of it”, and “was not in operation in the Congress party” at the time.

This attitude of wanting to bury its shameful past runs deep in the Congress party. In May 2019, Chairman of Indian Overseas Congress, Sam Pitroda, said, “What happened in 1984, happened.” Even when he later apologized under intense political and public pressure, he felt compelled to say it is time to “move on” and that there are “other issues to discuss”.

In 1992, the Babri Masjid mosque in Ayodhya was destroyed by the Hindu mobs, who were driven by the desire to recapture what they feel is Lord Ram’s birthplace. As early as the 1980s, the Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP) launched a campaign to build a temple at the site, with the support of the BJP. At the time, the state of Uttar Pradesh (UP), where the event took place, was ruled by Kalyan Singh, a BJP member, while the Congress party was in power at the national level. Prior to the event, PM Rajiv Gandhi approved the decision to allow Hindus to worship in the area. On the day of the event, in front of a crowd of over 150,000 people, BJP leader LK Advani and other prominent BJP politicians gathered at the site to symbolically announce that the construction of a Hindu temple would begin. The mosque itself was to remain untouched. However, VHP members and the BJP kar sevaks soon stormed past the gates, trampling over security forces and journalists to demolish the mosque. Close to two decades later, an inquiry by the Government of India determined that 68 people were responsible for the tragic event, including BJP leaders Atal Bihari Vajpayee, Advani, Murli Manohar Joshi, Vijay Raje Scindia, and Chief Minister (CM) Kalyan Singh.

However, neither the BJP nor Congress has offered a genuine apology for the demolition of the masjid. Vajpayee, who later went on to become the PM of the country, called the incident “unfortunate” and distanced himself from responsibility, saying, “We tried to prevent it, but we could not succeed,” and that it was “because a section of kar sevaks went out of control”. This ignores that just one day before the event, Vajpayee said even a Supreme Court “does not stop kar seva”, that there are “sharp stones there”, and that the “ground has to be leveled”. While his words do not directly incite mob violence or clearly advocate it, the ambiguity of his words can easily be misconstrued and considered to be permissive of “vigilantism”.

Similarly, while the former UP CM, Kalyan Singh, has since taken “moral responsibility” for the Babri Masjid demolition, he has failed to offer an apology. If Vajpayee and Singh were hesitant to offer an apology, then Advani was outright and explicitly dismissive, saying that while the demolition was the “saddest day of [his] life”, “the issue of an apology does not arise”.

In contrast, Congress politician Digvijay Singh has previously said “sorry to the nation for the demolition of the Babri Masjid as at that time the PV Narsimha Rao led-Congress was in power” at the Center. However, like several Indian politicians before and after him, he then shifted the blame to the BJP within the same breath, highlighting Kalyan Singh’s responsibility instead, removing any possibility of an unconditional apology.

In 2002, while Modi was the CM of Gujarat, a train carrying 60 Hindu pilgrims was set on fire. Enraged, Modi allegedly told senior police officers that Hindus should be allowed to “vent their anger”. What followed was essentially mass genocide, with official estimates stating that over 1,000 people were killed; independent sources suggest figures in excess of 2,000. The vast majority of those killed were Muslim. While Modi’s degree of culpability and complicity can be argued ad nauseum, it is clear, by his own admission, that his government was at the very least responsible for not adequately containing the bloodshed and controlling law and order in the state.

At the time of the incident, Tehelka, a weekly magazine, published covertly recorded videos of police officers and politicians bragging about “burning Muslim men, raping their wives, and destroying their homes”. In the sting operation, a BJP politician was recorded saying that the Chief Minister had told him they had three days to “do whatever we could”.

For years, Modi refused to even entertain the mere thought of an apology for the Gujarat riots. Only after 2010, once he started positioning himself as the BJP’s nominee for the Prime Ministership, did he even approach anything resembling an apology. In 2012, while giving a speech, he said, “If I committed any mistake, then I, my 6 crore Gujarati brothers and sisters, ask for your forgiveness.” However, a plea for forgiveness without any specific reference to what one is apologizing for, and one that puts the responsibility on and shifts the focus towards the aggrieved party, is disingenuous at best and remorseless at worst. In March 2013, it appeared that the tide had finally turned when Modi said, “innocent people were killed” and that “for that failing of the State government, I offer my unequivocal apology.”

However, hours later, he poured cold water on this long-overdue apology by saying, “Please read my statement carefully. Nowhere have I mentioned the 2002 events... My apology was only in respect of the 1969 and 1985 riots, which happened under Congress rule in the State.” In January 2014, Modi turned the focus back to himself, speaking of how he “single-mindedly focus[ed] all the strength given to [him] by the almighty” to deal with his own “grief, sadness, misery, pain, anguish, [and] agony” at seeing such “inhumanity”. By feigning victimization, Modi essentially distanced himself from responsibility by projecting himself as a bystander. In fact, he has previously said, “If someone else is driving a car and we’re sitting behind, even then if a puppy comes under the wheel, will it be painful or not? Of course it is. If I’m a chief minister or not, I’m a human being. If something bad happens anywhere, it is natural to be sad.” A chief minister is not a bystander in times of civil unrest, however, but an orchestrator or a protector.

This unapologetic nature is sewn into the fabric of the party and among its supporters. In 2014, Prakash Javadekar, a BJP spokesman, took it upon himself to speak for the victims of the riots, saying, “People have moved on,” when asked if Modi plans to apologize for the Gujarat riots. Moreover, before he retracted his “apology” in 2013, Modi’s followers on Twitter fell by half, with some commentators saying that they felt “betrayed” by a leader who has “shown himself to be a ‘sickular’ lamb” rather than the “unapologetic lion” that they thought he was.

This remorselessness is not only prevalent across political parties, but also across religious lines. There have been no apologies issued for various acts of violence against Hindus from those who were in power at the time or from the political parties that were involved. Such events include: the exodus of Kashmiri Hindus in 1990; the Godhra train burning incident in 2002, which preceded the Gujarat riots; the Marad massacre in 2003; and the Deganga riots in 2010. Instead, politicians like Engineer Rashid have said that Kashmiri Pandits must apologize for their own forced exile.

The Congress party has not apologized for rigging the 1987 Assembly elections to make Farooq Abdullah the CM of Jammu and Kashmir (J&K). Their combined corruption led to an increase in separatist movements–led in part by the Muslim United Front (MUF) and the Jammu Kashmir Liberation Front (JKLF)–that precipitated the attacks on, and the exodus of, the Kashmiri Pandits. Farooq Abdullah, who was CM at the time that the first Pandit was killed, has said nothing beyond meekly and rudely asking them to “come back”, saying that “they have to realize that nobody is going to come with a begging bowl and say come and stay with us”. If this is the kind of welcome that Kashmiri Pandits can expect, then it is clear that adequate reconciliation efforts have not been undertaken. In the past, Omar Abdullah, a former Chief Minister, son of Farooq Abdullah, and member of the same political party, Jammu & Kashmir National Conference (JKNF), has recommended setting up a Truth and Reconciliation Commission. However, nothing has come of this, save for an ultimately meaningless and contrived show of compassion.

Similarly, the BJP-backed Jagmohan Malhotra, whose appointment as Governor of Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) caused Farooq Abdullah to resign, has also failed to apologize for his role in the events. Jagmohan’s appointment came two days prior to the Gaw Kadal, Hawal, and Bijbehara massacres and the mass exodus of Kashmiri Pandits. Amid widespread unrest, including kidnappings, rapes, and murders, Kashmiri Hindus began contemplating leaving en-masse. Instead of providing them with the necessary security to continue living in the state, however, Jagmohan instead persuaded the Pandits to leave, telling them that “refugee camps had been sent up for them” and that he would “not be able to guarantee their safety” if they chose to stay. Essentially, he told the militant groups that they had won, facilitating the rise in terrorism that we see in the region today. Kashmiri Hindus were thus arguably used as pawns in a larger game of cementing Hindu-Muslim divisions. In the aftermath of this event, roughly 150,000 Pandits were displaced.

Indeed, there have been multiple incidents of violence against Hindus in India, such as: the Punjab killings in 1991; the Chamba, Wandhama, Chapnari, and Prankote massacres in 1998; the Amarnath pilgrimage massacre and the murder of Gurudev Shanti Kali in 2000; the Kishtwar massacre in 2001; the Qasim Nagar massacre and the attacks on the Akshardham and Raghunath temples in 2002; the Nandimarg massacre in 2003; the Doda massacre and the Varanasi bombings in 2006; and the Amarnath Yatra attack in 2017; among others. However, these events were perpetrated by terrorists, and expecting an apology from a terrorist group is naïve at best and foolish at worst. Nevertheless, it must equally be conceded that sections of the Indian population mourn and protest against the killings of terrorists such as Riyaz Naikoo, Zakir Musa, and Burhan Wani. While these sections of the Kashmiri population may not have directly participated in the actions of such groups, they are, in a sense, complicit in their actions through their vociferous support for the members of such groups.

Also Read: Are Right-Wing Democratic Politicians More Transparent Than Their Left-Wing Counterparts?

As George Orwell once said, “If thought corrupts language, language can also corrupt thought.” Similarly, politicians and constituents feed off of each other. Politicians put forth the ideologies and beliefs espoused by society, as they too exist as part of that society. Equally, people in positions of power have the ability to shape norms, culture, and discourse and to magnify and expand fractures in society. In India, it is unclear whether a culture of non-apology exists in civil society independent of politicians inculcating it. However, what is clear is that the religious divisions that guide this culture are amplified by politicians, who prey on our differences and incite endless cycles of violence and hatred.

It is for this reason that we are unlikely to witness any apologies for the current era in Indian politics and history–because there is no precedent, even after much more egregious events than what we’ve seen over the last six years. The unapologetic nature of Indian politicians is facilitated by the public, who chastise those who call for apologies by resorting to ‘whataboutism’. Criticism of rising Islamophobia, for instance, is regularly met with the retort of “What about the Kashmiri Pandits?”, as if one act excuses the other.

Reconciliatory efforts must thus be led by the government and politicians to usher in new political norms and culture in India. As seen in Germany, this yields numerous benefits both domestically and internationally. Canadian PM Justin Trudeau, for example, has unreservedly and unconditionally apologized for the horrors of the Komagata Maru incident and the atrocious treatment of Indigenous children in residential schools. It is actions like these that have shaped Canada’s global image as a champion of diversity, inclusivity, and human rights.

Conversely, the Indian government is on the receiving end of rising accusations of Islamophobia, most recently by Gulf countries and the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom’s (USCIRF). Regardless of the questionable validity of such accusations from states that are built on human rights abuses, and from commissions that seek to expand American hegemony, their criticisms are rooted in reality, and hence cannot be dismissed out of hand. Admitting that these problems do in fact exist, that the government is aware of them, and that it is working to address them would assuage international actors and accrue invaluable political capital. It would advance India’s goal of becoming a Vishwaguru and gaining a permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council by presenting India as a responsible and inclusive power. Moreover, it would project it as a viable future alternative to China and the United States for global governance, who are both unwilling to confront the horrors of their governance and their bloodied past and present. It is clear that safeguarding its international reputation is a key concern of the Indian government–else, it wouldn’t have tried to hide the Delhi riots from Trump. Accordingly, India cannot afford to ignore the benefits of admitting its shortcomings.

At the same time, a more apologetic approach can also yield domestic benefits, by quelling support for militant and separatist groups, reducing mob violence, and eliminating discriminatory consumer, hiring, and business practices. It can also engender greater camaraderie and harmony among India’s rich and diverse religious communities. The BJP might be able to mislead some international actors by extracting what resembles a forced confession from Minority Affairs Minister Mukhtar Abbas Naqvi, who said that “India is heaven for minorities and Muslims”, but it cannot deceive those minorities themselves, who are painfully and personally aware of the ground reality. Constructing an apology culture may also yield a domino effect, wherein we finally have an answer to the question “What about the Kashmiri Pandits?”.

A transformation of political norms and discourse is not something that happens overnight, however. At present, the benefits of apologizing are a distant and utopian reality for India. In the current scenario, one can argue that the ruling government is merely enabling or emboldening people to act upon deep-rooted, pre-existing beliefs. For example, Hindu lynch mobs openly admit that they are more active now because the “police is on [their] side because of the government”. Moreover, the political costs of embracing a culture of apology in India remain too great. For instance, when Modi offered an “apology” for the Gujarat riots, he lost half of his Twitter followers and was called a “sickular lamb”, forcing him to retract his “apology” almost immediately. India does not have a one-party system, and hence it follows that this culture, and the high costs of abandoning it, is something that has been nurtured across decades by multiple governments, parties, and leaders. Therefore, any efforts to drive a shift away from this ‘whataboutism’ and reticence to apologize once again require the buy-in and a collective effort from all political parties, for decades. The infusion of a reflective and self-critical political culture incentivizes and increases the likelihood of apologizing, and in doing so makes the domestic and international reconciliatory and healing benefits of apologizing far greater and far more attainable.

The Congress Party’s Sam Pitroda and the BJP’s Prakash Javadekar dismiss calls for apologies by unilaterally declaring that India has moved on from events like the anti-Sikh riots and the Gujarat riots. If they are truly interested in closing the book on India’s past and writing a new chapter, they must encourage their parties and their leaders to unconditionally apologize for past crimes, to engender closure, healing, trust, and reconciliation.

In April 2013, when Modi backtracked on his apology for the Gujarat Riots and said that he was actually apologizing for the 1969 and 1985 riots, he said, “There is a precedent for that”. He was referring to ex-PM Manmohan Singh’s apology for the 1984 anti-Sikh riots in 2005, which came 21 years after the event. Thus, he said, “Perhaps, as the Congress established, it needs the passage of time - of upto 20 years - for the wounds to heal and for an apology - even if it comes from someone else - to be accepted.” By his own standards, we must now wait until 2022 to see whether Modi apologizes for the 2002 Gujarat riots. However, given that he has said “Jitna kehna tha keh diya. (I have said everything I wanted to say) I have been exonerated by the people’s court”, one mustn’t get too excited. By his own admission, Modi recognizes the healing properties of apologizing–he just doesn’t want to do it. Until India elects a leader that is willing to foster a culture of apology, or such a politician emerges, domestic unrest will continue and the painful wounds of India’s past will continue to fester.