India is already facing a water crises and 21 cities of the country will soon see acute water shortage as per the reports of Composite Water Management Index (CWMI). After facing two consecutive years of weak monsoons, around 100 million people would be affected if India reaches the predicted zero groundwater level. The reports are already widely published, and media houses have discussed multiple possible solutions to it. There is still a gap in addressing the difficulties surrounding the institutional arrangements around the use of water and the legal framework of water management in the country.

In an article on Chennai Water Crisis, I had discussed how the water crisis is constructed when societal (human misuse of water) and ecological components (physical scarcity of water) interact. Rapid urbanisation and uncontrolled use of water have resulted in mismanagement of the resource. Water is viewed as an open-access resource, thereby leading to overuse and unchecked withdrawal of groundwater. The activists and researchers have widely discussed the privatisation of water. For this article, I interviewed Ms Gauri Noolkar-Oak, a transboundary water conflicts researcher who has studied river basins in the Middle East, Southeast Asia, and South Asia. She has discussed the possible ways to approach the water crisis. Ms Noolkar stresses the importance of a shift in the way the resource is governed.

1. India is facing a water crisis, and the growing urban population is a significant problem, we do understand this already; however, what we often fail to understand is the mismanagement of the resource. Could you let us know how mismanagement can be tackled?

We have to understand that domestic and industrial use constitute roughly 20% of all water use (and misuse) in the country. 80% of our water goes into agriculture, and that is also where the bulk of the wastage and mismanagement lie. Of course, that does not mean that the urban population is not causing problems; cities and factories are definitely responsible for water pollution through both domestic and industrial uses.

Deep down, we all know that it is the mismanagement of water that is leading to the crisis, but as in all other things, we are so set in our ways that it is going to take a lot to change. To tackle water mismanagement by cities immediately, we need metering of water use, appropriate pricing and strict implementation of the “polluter pays” principle, along with vigorous campaigning by CSOs and social leaders to change consumer behaviour.

Media support to both governmental measures as well as civil initiatives is equally crucial. However, to ensure the effectivity of these measures and initiatives, we need to vest our local government bodies with more powers and autonomy, which is not exactly an ‘immediate’ action, but certainly a most required one.

Also, one has to look at this realistically — effective (and this word is important) demand management is essentially holding people accountable for their behaviour and making them change their habits. Obviously, it is not going to be a popular move and can have serious political consequences. Would there be any democratically elected government willing to risk it?

2. Will the integrated body 'Ministry of Jal Shakti' be able to tackle the fragmentation in committees for water resources. How do you see the move? What according to you- decentralisation or a centralised ministry of the like, is suitable to tackle issues of water access in the country?

Fragmentation in managing water resources is an old problem, and it is too early to tell whether the recently integrated ministry will solve it. Also, integration must happen at the State level because water is a State subject. We still have separate departments/institutions dealing with agriculture, energy, environment, groundwater, fisheries, tourism etc. whose functions often overlap yet who function in silos even within the same river basin (and I am not including further divisions caused by political borders in the case or interstate rivers here). We need River Basin Organisations (and not just Irrigation Development Corporations which focus primarily on irrigation and thus have a narrow scope). Hopefully, the provision for 13 RBOs across the country in the upcoming River Basin Management Bill will solve this issue of fragmentation.

However in order to be effective, these RBOs must be given the broader mandate to carry out holistic river basin development by integrating the functions of providing drinking water, irrigating agricultural land, conserving rivers, their ecosystem and surrounding environment, securing local riparian livelihoods through activities such as fisheries and tourism, regulating other, related occupations (such as sand mining), and preserving quality and a minimum quantity of river water and groundwater. In that sense, RBOs would be a centralised structure.

In terms of spatial hierarchy, water management must be decentralised. This has been partially done; by categorising water as a State subject, the Constitution has already mandated states to have a more significant say in managing their waters. States should further devolve the authority and empower local government bodies to manage their water resources while they (the States) should be more in a supervisory and guiding role, particularly focusing on handling any water-related disputes that would arise within their territories.

3. Water is considered as a public good and available to all, unchecked use of groundwater and unchecked borewells are big issues. How water should be treated according to you, and what amendments are required in our legal structure?

Water is not just a public good; it is also a human right, as declared by the UN in 2010. However, almost two decades earlier, the (rather infamous) Dublin Principles stressed on the economics-based approach over the rights-based approach which the community of human rights activists and NGOs did not approve of fully.

As far as groundwater overuse is concerned, the issue is indeed challenging to tackle, at both policy and practical levels. Due to the vastness of our country, it is not practically possible to control groundwater abstraction everywhere. The invisibility of groundwater makes it further challenging to determine just how much of the total use is unwarranted. At the policy level, issues regarding ownership (and consequently, access and use) crop up. When groundwater aquifers cross state and national boundaries, the complexities deepen. British laws linked access and control of water to land and gave landowners pretty much-unlimited access to the water under the area they held. The spirit of these laws continues to complicate matters from local to transboundary level.

Water needs to be treated in two distinct but related ways- one, which combines rights as wells as economics, and two, which recognises it as a “common” resource.

Firstly, while water is indeed fundamental to human survival and dignity, after a certain level of consumption, its economic aspect must be brought into the picture. There is a point of use after which water turns from a human right to an economic resource, and we should not ignore that point; instead, we should devise policies and frameworks which take cognisance of this point and manage the allocation, pricing and consumption of water accordingly.

Secondly, understanding water as a “commons” can help address issues related to access, allocation and ownership, especially of groundwater. We have numerous examples of community ownership and management of resources, right here in India, both historical and contemporary. Treating water as a common resource which we, as a community ‘own’ along with other communities, seems to be an abstract idea, especially at a macro level, but at community levels, it is doable. Hence the need to decentralise water governance.

4. Armenia has set an example in providing free water to all, do you think a similar model is applicable in India, if not what best policies from the world our country can imitate?

Armenia used the PPP model, which is not a very encouraging story in our country. India experiences spatial and seasonal unevenness in the distribution of water, significant geographical, climatic and hydrological variations, and further diversity in socio-economic dynamics of water use. As such, there is no one policy or even a combination of strategies which India can adopt or imitate as a whole. Instead, we should look back at our past, especially in the pre-British eras when we had recognised the seasonality of our water supply, especially on the peninsula and incorporated it into our agriculture and economy. Water was then collected and stored at the local community level, in structures that were in sync with the topography and climate of the region. The concepts of “constant supply of water at high pressure within reach of every housewife’s thumb” and uniform availability of water all year round come with the British, and we have to look into the past, before the British, for policies, models and practices that suit our conditions.

5. At many places in Maharashtra, in housing societies and colonies, water supply is controlled, and residents receive it for a few hours in the morning and evening slot. Do you think this system helps manage water; if yes, why it is not widely implemented? What is the reason for the government's failure in managing resources?

The concept of 24*7 access to water directly in the house might have had some negative implications like complacency and wastage, but it is not realistic to say that we should go back on it. Controlling access to water by reducing the timeframe in which it would be available might work in the short term, but it will not give the desired results.

Instead of keeping water supply limited to a few hours, local government authorities must focus on measuring supply and consumption, minimising wastage, and appropriate pricing. Our water supply systems are poorly maintained and leaky, due to which around 30% of the water is wasted in the system itself. These systems need to be fixed on priority. The service of water supply must be priced enough to cover O&M costs. Effective procurement of this revenue requires accurate measurement of consumption and a competent revenue collection system. Whatever amount of water that can be recycled must be recycled and sent back for non-drinking domestic uses such as gardening and flushing toilets.

The government fails to manage resources like water in holistic ways because it has adopted an approach which is a) state-centric b) based on civil engineering and c) augmenting water supply. This alone tells you all that it has missed out. What about stakeholders other than the state — such as indigenous communities, women, industry, wildlife? What about non-engineering aspects of water — such as environment, biodiversity, culture, gender? What about functions beyond supply — such as demand management, river conservation, ecosystem protection, ensuring navigability, preservation for cultural/religious purposes? The government fails and will keep failing to manage water resources as long as it does not address these questions adequately through sustained actions.

6. How do you see India's water crisis interacting with the global water crisis? Where do we stand?

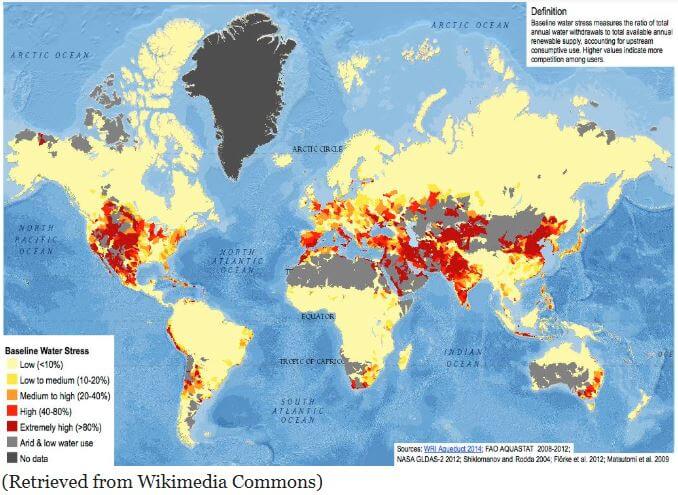

In terms of water scarcity and stress, it is no surprise that we are amongst the most critical regions on earth. Below is a world map which highlights regions withdrawing large quantities of water in bright red and dark red. India features prominently among these regions along with neighbouring Pakistan, Eastern China, Central Asia, the Middle East and Mid-west and Western parts of USA and Mexico. This belt is home to the most populated countries in the world, as well as extensive industry and agriculture. It is also geopolitically volatile.

Since water is fundamental to both survival and prosperity, any further increase in water stress is going to trigger more intense repercussions in these regions.

These repercussions are not going to be isolated. We must understand that the earth is one closed ecosystem and that the concept of “problems elsewhere are not our problems” doesn’t stand. Problems in other countries, especially those in our vicinity, are bound to impact us. If the flows of the Indus in Pakistan and the Ganga-Brahmaputra-Meghana in Bangladesh deplete beyond an acceptable level, people are going to migrate, and we cannot say for sure that India will not be affected. With the water crisis brewing in India as well, the sensitivity of migration-related issues ranging from personal trauma to demographic shifts will increase.

7. Lastly, the most important question, where does the solution lie?

There is a lot which needs to be done. India’s problems primarily lie in the approach towards governing and managing water resources. India should move from engineering-centric view to a multidisciplinary perspective; from centralised governance (state-centric) to decentralised governance (with multi-stakeholder participation); from a ‘development vs environment’ approach to a ‘development with environment’ approach. We need to redefine how we calculate our costs, revenues, profits and losses and include the costs of the river and environment degradation, as well as benefits of water and environment conservation in our developmental, infrastructure, industrial and agricultural activities. We need people to feel a sense of responsibility towards the water resources they use, and for that, concentrated and consistent efforts to change the mass perception and behaviour are crucial.

We need to stop viewing nature and technology (and nature and development) from the “either-or” lens. Water conservation methods and structures in pre-British India were also technology. Measures like rainwater harvesting, groundwater replenishment, river quality maintenance also require technology. Drip irrigation and sprinkler irrigation are technology-based solutions minimising irrigation water wastage.

The idea is to oppose indiscriminate use of large-scale technology, and not the technology itself, for that would lead to no effective results. Just as politicians and technocrats need to realise that growth and development need not happen at the cost of the environment, environmentalists to need to recognise that turning growth, development and technology into villains will not help, as it will not only limit their effectivity but will also alienate them from the common public. We must be embracing both nature and technology and encourage our scientists to work on devising solutions which do the same.

Cover Image Courtsey: PBS

-x-

Gauri Noolkar-Oak is a transboundary water conflicts researcher and has studied river basins in the Middle East, Southeast Asia, and South Asia. She is also a co-founder of The Tilak Chronicle and tweets @curiousriparian.