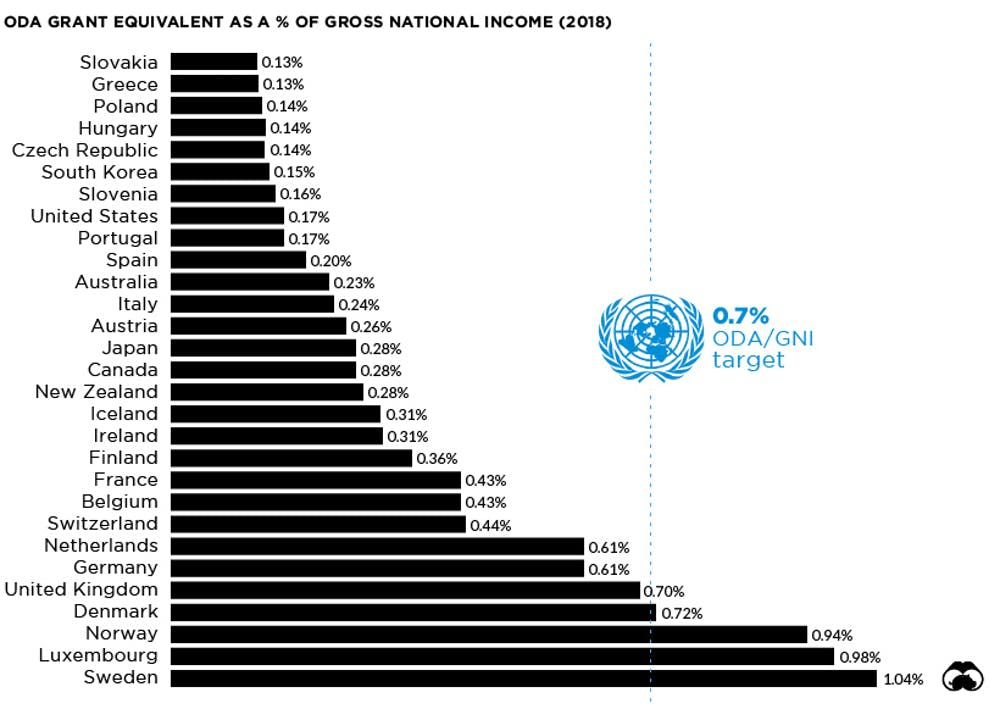

The United Kingdom’s (UK) Chancellor of the Exchequer, Rishi Sunak, announced this week that Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s administration would be introducing cuts to its overseas aid budget due to the economic impact of the ongoing coronavirus pandemic. Sunak said that the Tories would be reducing the overseas aid budget by one third, thereby breaking the ruling party’s manifesto, which assures that the government will spend 0.7% of gross national income (GNI) on foreign aid.

The decision has generated consternation both within and outside the Johnson administration, with foreign office minister and political adviser Baroness Elizabeth Sugg announcing her resignation in protest. Sunak, however, has countered and said that the government is in a tough spot due to the coronavirus pandemic, which has forced it to borrow a ‘peacetime record’ of £400 billion to reduce the impact of the “worst recession in more than 300 years”.

Lady Sugg wrote in her resignation letter that the UK must not “reduce our support further at a time of unprecedented global crises”. Sunak, though, argues that “sticking rigidly” to the 0.7% figure is not wise in the current economic environment, and said that the aid amount would be reduced to 0.5% of the UK’s GNI.

Other critics say that this will do significant damage to the UK’s credibility and reputation as a global leader. The Johnson administration recently joined the European Union (EU) China, Japan, and South Korea in adopting a net-zero emissions target for 2050 (although China’s target is set at 2060). More crucially, this comes ahead of COP26, or the 2021 United Nations (UN) Climate Change Conference, which Britain is set to host in Glasgow. Given its leadership role in this initiative, it is troubling that the UK has taken a step back from assisting other countries in achieving this vision.

It is estimated that developing countries require a minimum of $400 billion a year to cut their emissions to a level that is consistent with the targets set by UK and the like. Hence, the foreign aid they receive goes a long way towards helping them at least attempt to reach the goal of reducing their carbon footprint.

Accordingly, Tobias Ellwood, the chairperson of the Tory’s defense select committee, said that the UK cannot make claims to being a global power “when our hard power is not matched by soft power”. The seismic shift in policy contravenes a target that was first adopted as a ‘principle’ in 1974 and then signed into law in 2015 under erstwhile PM David Cameron.

To put things into perspective, aside from the damage it could do to the UK’s image, it is estimated that the withdrawal of British aid would more tangibly result in over one million girls missing out on receiving an education, three million women and children losing out on ‘life-saving nutrition’, 5.6 million children being left unvaccinated, and ultimately around 100,000 deaths.

During the preliminary stages of the coronavirus outbreak, the IMF estimated that poor and developing countries would require $2.5 trillion in financial assistance. Similarly, the International Labour Organization (ILO) estimates a loss of over 300 million full-time jobs due to the pandemic. The World Food Programme (WFP) calculated that more than 265 million people are at risk of malnutrition. Likewise, the United Nations (UN) warns that over 400 million people now face poverty.

As the pandemic has worn on and its economic impact has multiplied, these same humanitarian crises have only become more acute. Therefore, the UK turning its back on millions of vulnerable global citizens at this time could be characterized as a gross dereliction of duty and absence of conscience, particularly given that Britain’s colonial history played such a large role in crystallizing many of the inequities that are rife in today’s world.

The Johnson administration has remained steadfast in the face of this disapproval, saying that the cuts would free up £4 billion during what it describes as a “domestic fiscal emergency”. Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab has also stressed that the UK’s position as “one of the leading countries on aid […] will continue”.

However, it is telling that a Kingdom that is built on the labor and wealth of others has simultaneously increased its defense spending by £24 billion—money which it says it cannot spare for the world’s most helpless citizens.

This is not to say that Britain doesn’t have problems of its own that it needs to solve. Unemployment in Britain is expected to peak in the second fiscal quarter of 2021 at 7.5%, or 2.6 million people. Furthermore, its economy is forecasted to contract by 11.3% this year, and its economic recovery is expected to last until at least late 2022. However, economic experts suggest that this goal of recovery could have been achieved would reducing Britain’s overseas aid spending, which is only further evidenced by the fact that the government has increased defence spending by such a large amount at the same time.