On December 11, the Indian parliament passed the Citizenship (Amendment) Bill, drawing criticism and agitation across the nation as well as the globe. Protests were met with brutal police crackdown at the Jamia Milia Islamia University and the Aligarh Muslim University (AMU).

Reports indicate police using lathi-charges, firing tear gas and rubber bullets, and physically and verbally abusing female students. In Jamia, 52 students were detained at midnight; in AMU, 100 students were detained and more than 100 were injured. Reports suggest that injured students were denied medical assistance by police.

Leaders of the ruling party, including the Prime Minister (PM), dismissed the student protests as anti-national and anti-democratic. Leaders whose political careers were built on student activism and campus politics now admonish students for doing the same.

In 1974, PM Narendra Modi actively participated in Navnirman Aandloan, a student-led movement against the state, as an associate of Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad (ABVP). The protests were characterized by the destruction of public property and attacks on police personnel.

Their actions helped the leaders of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) and ABVP to gain a significant political foothold. In the same year, Jayaprakash Narayan called for a sampoorna kranti against the elected government. The movement led to the origin of the Bhartiya Janta Party (BJP), with ABVP as its student wing.

Thus, by condemning and terming these protests as sectarian and anti-national, BJP is turning its back on its own history. However, as those same people are now in the seat of power, non-conformist and anti-establishment students are vilified and targeted.

In fact, India has a long and storied history of student activism. For instance, the Indian National Congress (INC), formed in 1855, established its Student’s Association in 1875. The history of student activism in India can be traced to nationalist movements and freedom struggle.

In more recent times, students have agitated against the increased ferry boat charges, which later merged with the liberation movement against the communist government of Namboodiripad. They have marched against the Patnaik government in Orissa. And they have fiercely opposed the imposition of Bengali in Assam and Hindi in Tamil Nadu.

Student activism has steered public discourse and influenced state policies. For example, in the Hok Kolorob movement, students stood in unison against the molestation of a female student at Jadavpur University in West Bengal. In the Justice for Rohith protests, students demanded justice for the death of a Dalit student in the University of Hyderabad.

Thus, student activism at JNU against ABVP and the CAA is not a new phenomenon. Students have historically used their voice to actively contribute to the process of political socialization.

India is a diverse and stratified nation; several societal and political developments directly or indirectly affect the student population. However, their political freedom and agency are now threatened by growing state intolerance against anti-establishment and non-conformist student activism.

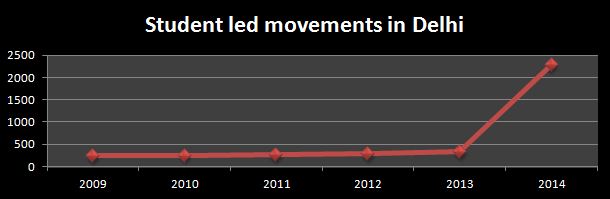

According to the reports from the Ministry of Home Affairs and Bureau of Police Research & Development (BPRD), student-led movements in India recorded rose 148% between 2009 and 2014. The State of Delhi, for instance, recorded a surge in student-led movement as shown in the graph below:

Reactions to student protests are highly dependent on political and socioeconomic factors. Those who are at the fringes of social power and don’t align with the government’s policies see student activism as one of the pillars of liberal democracy, while those who are at the core of social power and do align with the government’s policies tend to term student protests as disruptive.

Nevertheless, the influence of students is acknowledged by all. The state considers students a powerful political force and has thus used institutional violence and academic disruptions to suppress them.

The New Education Policy underlines restrictions on universities and students to curb political activities on the campuses and advises universities to focus on the ‘primary purpose’ of the education. The policy also advises banning student associations based on caste, religion or political affiliations.

Nevertheless, the Kerala government recently passed a draft bill that aims to remove restrictions on student politics on college campuses, arguing that such restrictions violate the fundamental rights of citizens and students.

In spite of such measures, the students are now routinely targeted through legal, physical, and verbal intimation. Student protestors are routinely being charged with sedition, violently attacked, and called anti-nationals. By portraying students as a threat to the unity of the country, the incumbent government has eroded the autonomy of students and educational institutions and undermined their political agency.

By threatening the democratic fabric of the nation, the government has triggered and intensified social unrest, and inculcated a sense of alienation and distrust in the state.

In response to the Navnirman Aandloan, the Congress-led government resorted to using police brutality to suppress political dissent and student activism. The State detained and blacklisted student leaders from opposition parties, and often denied them admission to state universities. Elections for student unions were banned. The state also passed ordinances to curb the autonomy of educational institutes and increase state interference. For instance, at JNU in 1975, student union elections were called off and the right to protest was revoked. The former president of the university’s student union was suspended and then detained under the Maintenance of Internal Security Act.

Thus, during the Emergency era, and indeed across Indian history, students have heavily contributed to shifting the currents of Indian politics. Although the state attempted to suppress their voice, student activism played a crucial role in defeating the ruling Congress party in the Lok Sabha elections.

In a sense, history is now repeating itself. But now, the oppressed have become the oppressors.