In recent months, North and South Korea have made considerable progress in thawing relations that have remained hostile for the most part since the Korean War. In July, the two reconnected hotlines across the demilitarised zone after a disconnect of nearly 14 months. In addition, the two have been in talks to reopen a joint liaison office that Pyongyang demolished last year and to hold a joint summit.

While these positive developments have been encouraging, efforts to restore ties remain fragile, particularly in light of the fact that little has been done to address the trust deficit between Seoul and Pyongyang. In fact, recent initiatives for reconciliation were dealt another blow as South Korean troops began training with the United States (US) military last month. The military drill involved combined command post training focused on computerised simulations to prepare the militaries of the two allies for various battle scenarios, such as a surprise North Korean attack.

Kim Yo-Jong, the Vice Department Director of the Central Committee of the Workers’ Party of Korea and Supreme Leader Kim Jong-Un’s sister, released a statement warning that the South’s participation in the drills will “seriously undermine” any progress made so far. Since it was confirmed that Seoul would go ahead with the planned drills, Pyongyang has stopped answering routine calls on the inter-Korean hotline.

However, even if South Korea had acceded to North Korea’s demands to cancel the drills, it is unlikely that Pyongyang would remain appeased in the long run. Washington, Pyongyang, and Seoul all want peace and stability on the Korean peninsula, but all three hold a different definition of what this would entail. In this respect, the fact that none of the parties can agree on common objectives and that they all have unrealistic and severely divergent expectations of one another has significantly undermined any possibility of conflict resolution.

The US’ presence on the Korean peninsula threatens North Korea as much as it reassures the South. “For peace to settle on the peninsula, it is imperative for the US to withdraw its aggression troops and war hardware deployed in South Korea,” Kim Yo-Jong has said.

However, for the US, a complete withdrawal of its troops from the region would mean an overhaul of its Indo-Pacific strategy and bring with it a disadvantage in tackling regional contingencies, including a possible conflict with China. Moreover, while Seoul doesn’t have its own nuclear weapons, Pyongyang does, and is theoretically capable of targeting the continental US, Guam, and the US’ closest Asian allies, including South Korea and Japan. With so much at stake, pulling out troops from its bases in South Korea is not a concession that Washington can afford to Pyongyang.

Meanwhile, the US has been bargaining for the complete denuclearisation of North Korea, an issue that is indispensable to Pyongyang’s defence aspirations. In order to achieve this goal, Washington has employed a two-pronged strategy economic sanctions and arms control talks. The sanctions have placed inordinate pressure on North Korea’s already highly vulnerable economy, especially during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

Under US sanctions, North Korea is unable to sell its most crucial export goods, including coal, iron ore, and various natural resources. In 2018, Chinese imports from North Korea plummeted by 88%. Although Chinese trade data is not always fully reliable, particularly on imports of sanctioned goods from North Korea that could have been smuggled, it’s unlikely that Beijing would have imported any significantly large quantities of coal from North Korea and simply left them unaccounted for in the books. With China being the North’s main economic lifeline, these exports are likely a crucial source of funding for Kim Jong-un’s regime. Against this backdrop, North Korea is reportedly suffering from large scale food starvation as a result of US sanctions.

However, despite these economic challenges, it is clear that the pressure of sanctions has had little effect on Washington and Seoul’s joint push for denuclearisation. In February this year, North Korea’s former acting ambassador to Kuwait, Ryu Hyeon-woo, said that for Kim, nuclear weapons are “key” to his survival and the belief that North Korea’s status as a nuclear power “is directly linked to the stability of the regime.” The diplomat is among the many who believe that Kim will not be willing to give up his nuclear arsenal completely, but may be open to negotiating an arms reduction plan in exchange for sanctions relief.

While South Korea wishes to bring Pyongyang to the negotiating table and get it to dismantle its nuclear weapons, which put Seoul well within its reach, it wants to accomplish this with the help of its ally, Washington. Naturally, Pyongyang is reluctant to look past its severe distrust of Washington. Moreover, it also wants the South to unilaterally break sanctions, which Seoul isn’t willing to do without permission from the US.

Under these circumstances, it is not surprising that Pyongyang wants nothing to do with the South Korean government. According to Cheong Seong-chang, an analyst at the Sejong Institute in Seoul, Moon is just not “pro-North” enough for Kim Jong Un. If Moon was truly pro-North, it “would have stopped the joint US-South Korean military exercises as asked and stopped the import of stealth fighters which can attack North Korea without being detected,” explains Cheong.

This goes to validate that a phased approach is necessary for all parties. Outcomes of a more realistic and flexible form of diplomacy will be critical to the region as a whole and could serve to repair trust that has been broken several times over. Ultimately, complete denuclearisation appears to be a lofty goal given that it is intrinsically linked to national identity and regime survival. Similarly, however, the complete withdrawal of sanctions cannot be achieved without some compromise in arms control talks. In this respect, North Korea, South Korea, and the US must all seek to compromise in order to achieve at least some of their highly divergent goals. In the absence of this flexibility, reconciliation, denuclearisation, and the withdrawal of sanctions will all remain unattainable.

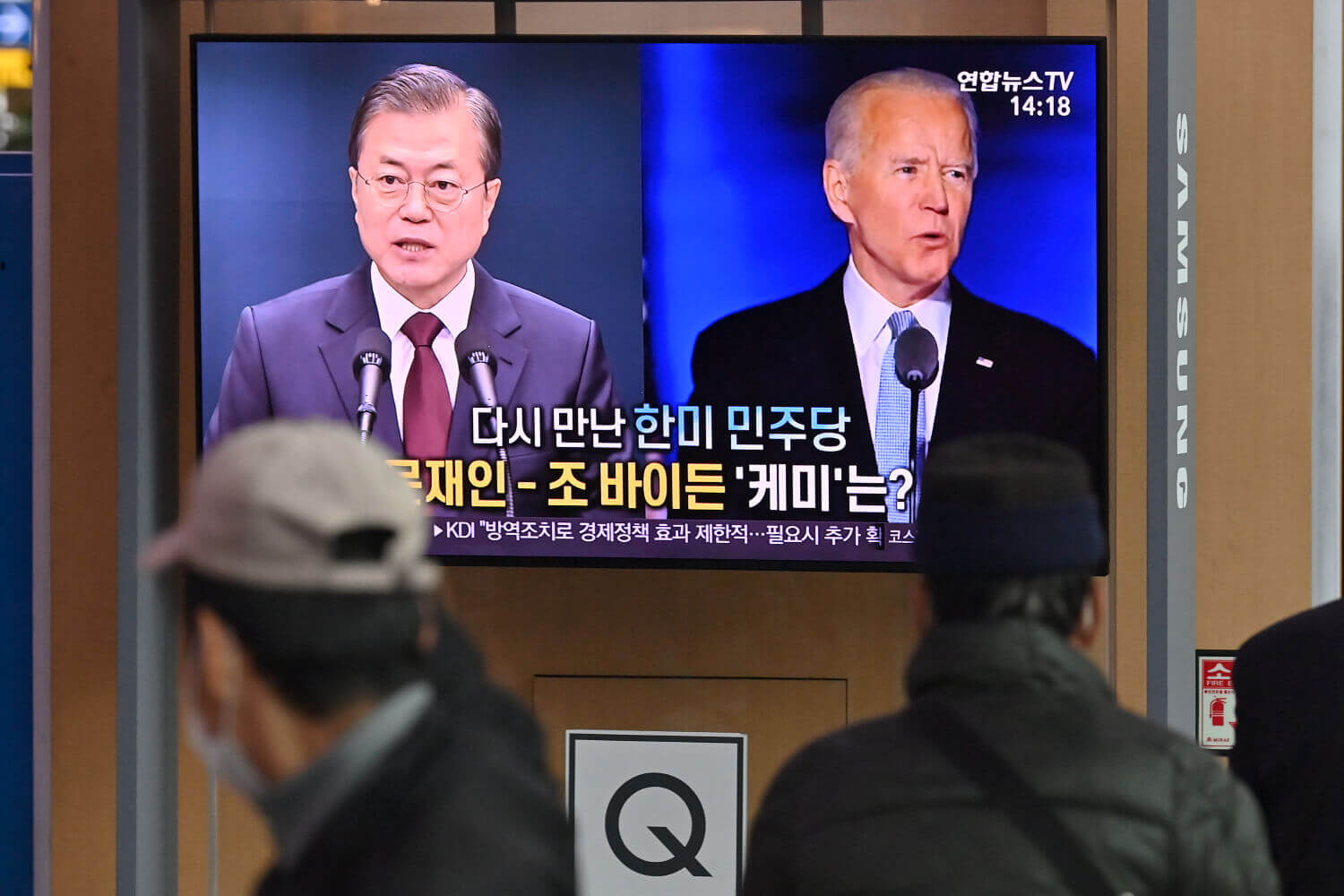

South Korea and the US Need a More Realistic Approach to North Korea’s Denuclearisation

The United States and South Korea need to gradually phase out the denuclearisation and build trust to prevent negotiations with North Korea from falling through again.

September 3, 2021

SOURCE: JUNG YEON-JE/AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES