India terms itself a ‘secular’ state; the Indian Constitution guarantees legal equality to all its citizens irrespective of their religious beliefs and practices and prohibits any kind of discrimination on the basis of religion.

The idea of secularism is used as a vanguard to celebrate the plurality and diversity of Indian society. However, the varying interpretations over the meaning of ‘secularism’ create conflicts between minority rights and secular principles.

The Indian Constitution does clearly not define the term ‘minority’. Article 29 and 30 primarily refer to linguistic and religious minorities. The Central Government of India recognizes six religious communities as minorities in India: Muslims, Christians, Zoroastrians, Sikhs, Buddhists and Jains. It is argued that the implementation of affirmative policies for religious minorities favours one community over another, and goes against the secular ideology of the nation; thus, religious minorities are excluded from the ambit of affirmative policies of the state.

The reservation system which facilitates the accessibility to seats in government jobs, educational institutes and legislatures is restricted on the basis of caste identities. The state initially restricted the reservation to Scheduled Castes (SC) only for Hindus, on the grounds that the caste system was peculiar to Hinduism. Later, it was extended to Buddhists and Sikhs with the state arguing that those religions are an extension of Hinduism.

However, the 1955 Kaka Kalekar Commission and the 1980 Mandal Commission acknowledged that the caste system is not restricted to Hinduism; there are several Muslims who fall under the 'backward classes' category as Muslims are not a monolithic community. In fact, According to National Sample Survey Office (NSSO) data, Muslims constitute 6.4% of the total Other Backward Class (OBCs) population. Thus, with the implementation of Mandal Commission Report, Muslims and other religious groups who fall under the caste system were provided with the OBC reservation benefits.

Reservation based solely on religion faced judicial resistance and is derailed further by constitutional discrimination. Both the Andhra Pradesh and Bombay High Courts struck down reservation and quota requirements for the Muslim community. Furthermore, although the Supreme Court ruled that Dalit Muslims and Dalit Christians are also entitled to reservations in 2015, it was stipulated that they must reconvert to Hinduism in order to access these benefits.

State policies have also been inefficient in uplifting minorities, thus exacerbating the institutionalized deprivation of the Muslim community. For example, the Prime Minister’s 15-point program for the welfare of minorities was formulated in the year 2006. The program was a package of several schemes addressing the development deficits in the districts with high minority concentrations. It was aimed to provide socio-economic aid and infrastructure to the minorities. However, most of the policies remain either ineffective or absent.

The merits of implementing affirmative policies for backward classes, particularly for the Muslim community, are seen in Kerala and Karnataka. Kerala was the first Indian state to introduce reservation policies that specifically included the Muslim community. Consequently, Muslims in Kerala have the highest literacy rate among all the states. In Karnataka, Muslims with an income of less than Rs.2 lakh per annum were placed under the ‘more backwards’ category and were provided 4% of seats in educational institutions. Reports show that Karnataka has seen a significant rise in Muslim enrollment in professional courses and employment in the state government.

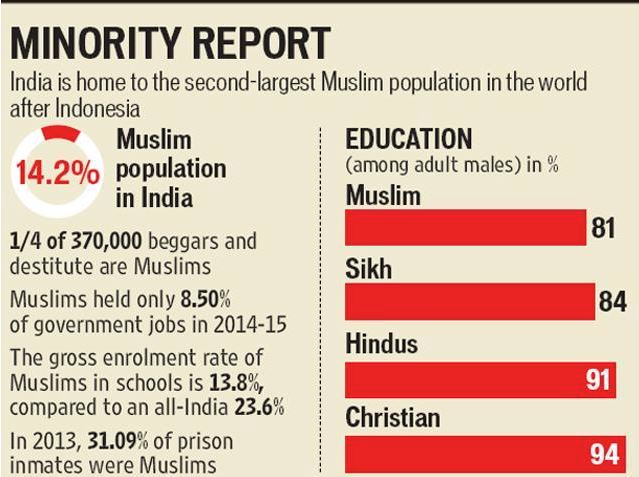

Nevertheless, socio-economic and educational statistics show that such policies have done little to alleviate the systemic inequality. Indian Muslims are among the most deprived communities and poorest among all religious groups. They have the lowest living standard, with an average per capita expenditure of Rs. 32.66 a day. Conversely, the average per capita spending of Hindus is Rs. 37.50, Rs. 51.43 for Christians and Rs.55.30 for Sikhs. They have the lowest worker-population ratio–and the majority of them are working in the informal workforce or are self-employed–due to a lack of educational opportunities. Muslims also have the highest illiteracy rate of 42.7%, compared to 25.6% for Hindus, and 32.5% for Christians and Sikhs.

Their plight is magnified by the fact that they lack political representation to improve their situation, and their marginalization is amplified by the growing Islamophobia in the country. Consequently, Muslim representation in the parliament is at a 50 year low and has shrunk from 9% in 1980 to 4% in 2014.

Unfortunately, India is not an exception with its growing trend of Islamophobia. Muslims around the globe are increasingly being subjected to exclusion, discrimination and violence. They constitute almost 24% of the world population, yet are victims of worldwide exclusion and marginalization. For example, in 2017, the United States issued a travel ban on several countries with a majority-Muslim population, like Yemen, Somalia, Iran, Libya, Syria and Chad. The Muslim unemployment rate in the UK and France is the highest among all religious groups; in France, 30% of Muslims are unemployed. Their income is also lower than the national average in all European countries. In addition, their ability to escape cyclical poverty is undermined by the fact that only 32% and 25% of Muslims achieve university education in the UK and France respectively.

Thus, Muslims across the globe are subject to systematic and continuous exclusion. And state mechanisms, despite being democratic, plural and secular in nature have failed to address these challenges. In the case of India, it is clearly indicated that the inclusion of the Muslim community in the backward class has not resulted in any significant affluence. In fact, there has been a further widening of the socio-economic gap between Muslims and other religious communities.

It is also pertinent to understand is that Muslims in India are not a homogenous category. For example, it is argued that preferential treatment for the entire Muslims community as a backward class in educational institutes will be an effective way to address the growing marginalization of the community. However, this move has faced resentment from the lower caste Muslims who are already enlisted in the OBC category. At the same time, fallacies of reservation policies and its implementation cannot be overlooked.

Simultaneously, a system of preferential treatment to a religious community stands in contradiction with the idea of secularism. On the one hand, the Constitution prohibits any kind of discrimination on the basis of religion; hence debarring reservation on the basis of religion; on the other, it provides the provision of affirmative action and positive discrimination for socially and educationally backward classes. Thus, what is required is to provide social justice in a manner which is constitutionally valid and judicially justified. To achieve this, it is indispensable to first understand the social structure of the Muslim community and the stratification that exists within it. Therefore, in order to remove structural impediments to economic mobility, it is not only vital to redefine and expand our understanding of secularism, but also understand the intricacies of these minorities and their varying, diverse concerns.