The ongoing global male fertility crisis has taken population experts by storm in recent years. Several developed countries, such as Japan and Canada, have already been facing the grave economic repercussions of an increasingly ageing population owing to low fertility rates.

On the flipside, in developing countries like India, which has long struggled with population control, policymakers seem to have dedicated their resources to regulating and limiting female fertility to control overpopulation, as opposed to addressing male infertility to check undesirable demographic changes such as a gradually ageing population with a reducing workforce.

This looming crisis may be solved by raising awareness and implementing urgent reforms in India’s family planning policy, such that it is in keeping with the global and domestic demographic challenges.

The Global Infertility Crisis

Infertility is clinically identifiable “in women and men who cannot achieve pregnancy after 1 year of having intercourse without using birth control, and in women who have two or more failed pregnancies.”

Several experts have warned about the ongoing “reproductive crisis” caused by a growing number of incidents of infertility attributed to the catastrophic drop in sperm counts worldwide.

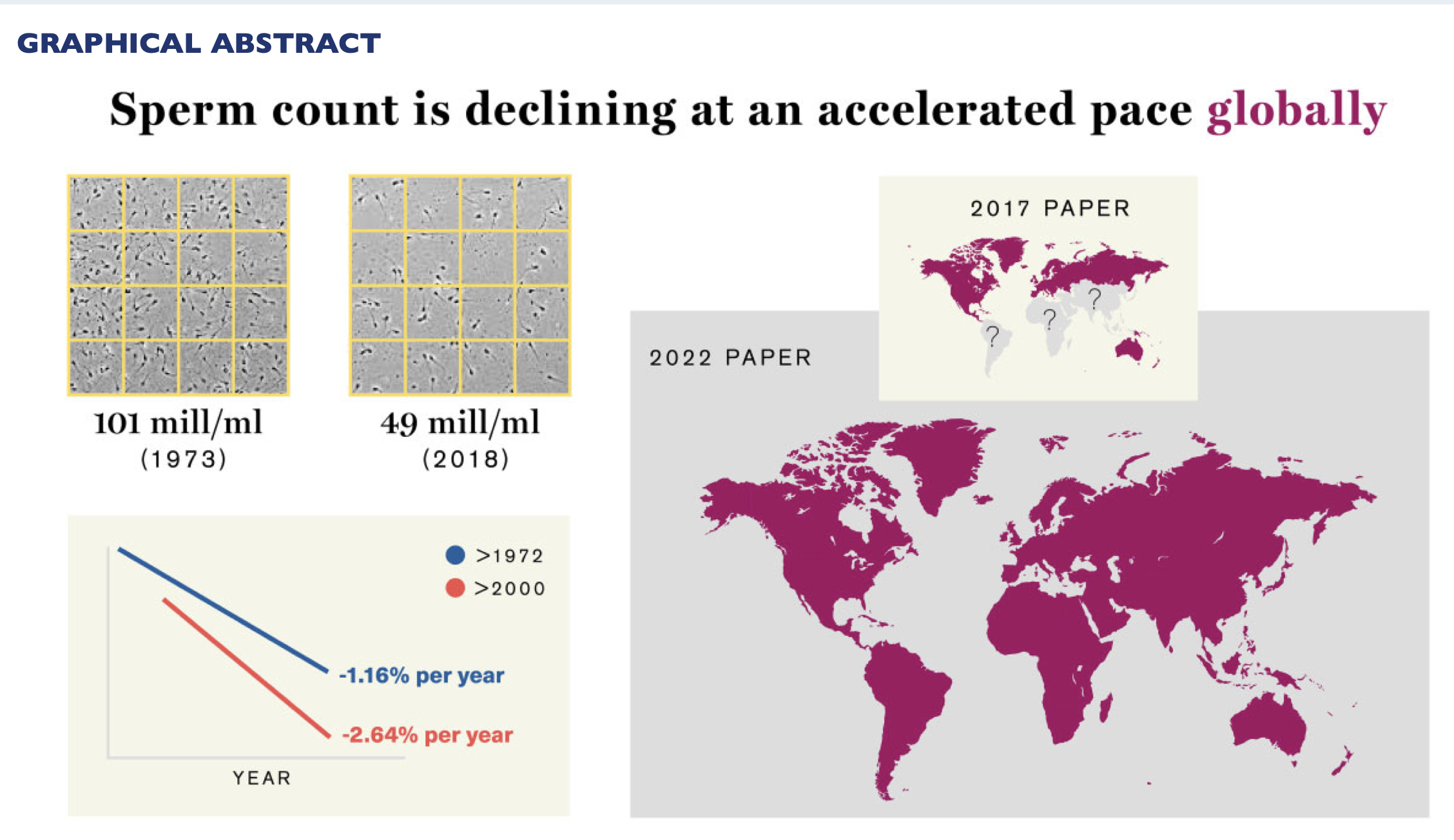

According to a 2017 study, the average sperm count in Western countries, which were the only countries that maintained data on this issue for several decades, dropped by over 50% from 1973 to 2011. However, a detailed study published in November 2022 confirmed that this trend is uniform globally, including countries in Asia, South America, and Africa, which have had historically high population growth.

The drop in sperm quality and count is a consequence of several environmental and lifestyle factors. For instance, one possible reason for this phenomenon is the increased exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals, which are present in products including plastics and shampoos. In addition, increasing cases of obesity and diabetes, along with a surge in the consumption of alcohol and tobacco, are contributing to a decline in male fertility rates.

India’s Case

India has been unable to escape this frightening trend as well. Several doctors and medical experts have confirmed that there is a drop in Indian seminal quality, with around 10% to 15% of couples who approach healthcare experts reportedly having fertility issues.

In addition, subject experts have raised concerns about the gradually ageing Indian population, which has been lauded as the youngest in the past. For instance, the average age in India has risen from 21 in 1947, to 28 in 2022. While merely 5% of the population was aged over 60 in 1947, that statistic surged to 10% in 2022. Concerningly, this means that the size of India’s working population, which includes those aged 15 to 64 years, is significantly reducing as the average age increases.

These numbers do not appear to be as alarming as those of Western countries with much older populations, like the UK, and other more industrialised countries like Japan. However, given that finance experts have linked an older population to stagnated economic growth, Indian policymakers need to learn from the experience of their Western counterparts to avoid going down the same path.

Thus far, India has relied on Total Fertility Rate (TFR) as a metric to determine the success of its family planning and population control policies. In 1947, the TFR was at 6 — worryingly higher than the replacement level fertility of 2.1, at which a population exactly replaces itself from one generation to the next. Years of population control policies, including repressive measures such as forced vasectomies and target-based tubectomies, finally brought TFR down to 2.0 in 2019-2020.

Obsessing Over Population Control

Despite its success in bringing down the TFR, India continues to consider overpopulation as a major problem, and treats it by managing female fertility, instead of addressing the ageing population and reduction in workforce, which are partly due to a male infertility crisis.

Moreover, several states — including Uttar Pradesh (UP), Madhya Pradesh, Karnataka, Uttarakhand, Tripura, and Assam — are still considering introducing laws to curb population by limiting access to welfare benefits and government jobs.

Two historical factors — the Malthusian theory and a focus on female fertility at the expense of overlooking male infertility — underlie India’s family planning policies and are to blame for the ignorance regarding demographic issues plaguing its population.

First, India’s approach to its family planning policies is largely driven by the West-advocated Malthusian approach to population science, which posits an inverse relationship between living standards and population.

To this end, since independence in 1947, successive Indian governments have been obsessed with population control, with each government adopting a variety of measures to bring down the “exploding” population. This fear continues to haunt policymaking in India, which was further exaggerated by July’s UN report predicting that India’s population will cross 1.6 billion by 2050, far exceeding China’s 1.3 billion around the same time.

India just passed China as the most populous country in the world. Why?

— Tomas Pueyo (@tomaspueyo) February 7, 2023

Because of the biggest accident in history

Look at where people live in India. What's that band up north? pic.twitter.com/91Atp9t8HL

The Malthusian theory has been popular among most countries in the Global South, particularly against the backdrop of less densely populated Western countries’ growing economies and global influence. Only in the last decade or so, when countries like India and China emerged as major global economies, the theory began to be questioned.

However, the government continues to view India’s family planning problem as one of over-fertility instead of taking a more wholesome understanding of reproductive health and assessing the extent and implications of infertility.

Second, India has often deployed a majority of its resources to check, regulate, and control female fertility, thereby causing male fertility to be an undocumented and unaddressed issue. Experts often complain about the lack of data on male infertility, which makes it difficult to assess the extent of the crisis.

India remains fixated on using female sterilisation as a primary means to assert its family planning policy, which essentially demands curbing fertility.

MoS for @MoHFW_INDIA @AnupriyaSPatel briefed in a written reply in #RajyaSabha about Government Programmes to Encourage Sterilisation

— PIB India (@PIB_India) July 31, 2018

📖https://t.co/OwNl0m3LNU pic.twitter.com/gxQwgns2OJ

For instance, while India succeeded in bringing the use of modern contraception up from 47.8% in 2015-2016 to 56.5% in 2019-2020, the use of female sterilisation also hiked from 36.0% to 37.9% during the same period. In addition, a 2021 study highlighted that India spent 85% of its family planning budget on female sterilisations.

Path Forward

Hence, the combination of India’s age-old obsession with controlling fertility, and the use of female sterilisation as a government-supported form of contraception, has resulted in its failure to acknowledge the looming “infertility” crisis, particularly that pertaining to men, and ignorance of certain demographic challenges.

A look by @TheEconomist at demographic comparison (using @UN data) between China (population peaking) and India (population overtaking China’s) pic.twitter.com/lxxIbbXSgz

— Liz Ann Sonders (@LizAnnSonders) January 11, 2023

Even after India’s policymakers acknowledge the need to simultaneously address the infertility crisis, it has several battles to fight. In Indian societies, male infertility is often associated with a loss of ‘manhood.’ Hence, it could prove challenging to raise awareness, given the social stigma surrounding the discussion.

In this regard, India’s path to dealing with the male infertility crisis, or the reproductive crisis, is one that requires long-term changes in mind frames and sensitivities. A successful campaign will demand years of education and awareness drives, as well as training of healthcare workers, to engender a shift in people’s attitudes towards the issue.

If India does not recognise the need to change its family planning policy, abandon its obsession with female “fertility,” and acknowledge the threat of male “infertility,” it could soon follow the path of other countries that are struggling to contain their ageing population due to a delay in identifying the issue and implementing relevant measures to address it.