Brain drain — the emigration of highly skilled, qualified, and educated people to countries with more opportunities — has historically plagued poorer or developing countries globally. A significant and increasingly relevant example of this phenomenon is that of India.

For decades, millions of young Indian students and workers have chosen to travel abroad to obtain a superior higher education, better-paying jobs, richer standards of living, or simply out of cultural attraction. Initially, this was beneficial for the most part, as studying or working abroad was used as a means to an end. Many students chose to get their degrees and work abroad for a few years before returning to India and utilising their new-found knowledge and experience to take the lead in a developing economy, market, and corporate environment.

However, with recent reports suggesting that over 75% of the emigrating Indians choose to stay back in the US, or other developed countries, after completing their studies, there is a need to seriously assess the negative externalities this trend may imply.

While several countries, both ‘developed’ and ‘developing,’ would much rather retain top talent and skilled workers to maintain a competitive edge against the backdrop of ever-accelerating globalisation, we must look for ways to harness the inevitable outflow and inflow of individuals in search of a variety of opportunities.

Historical Background

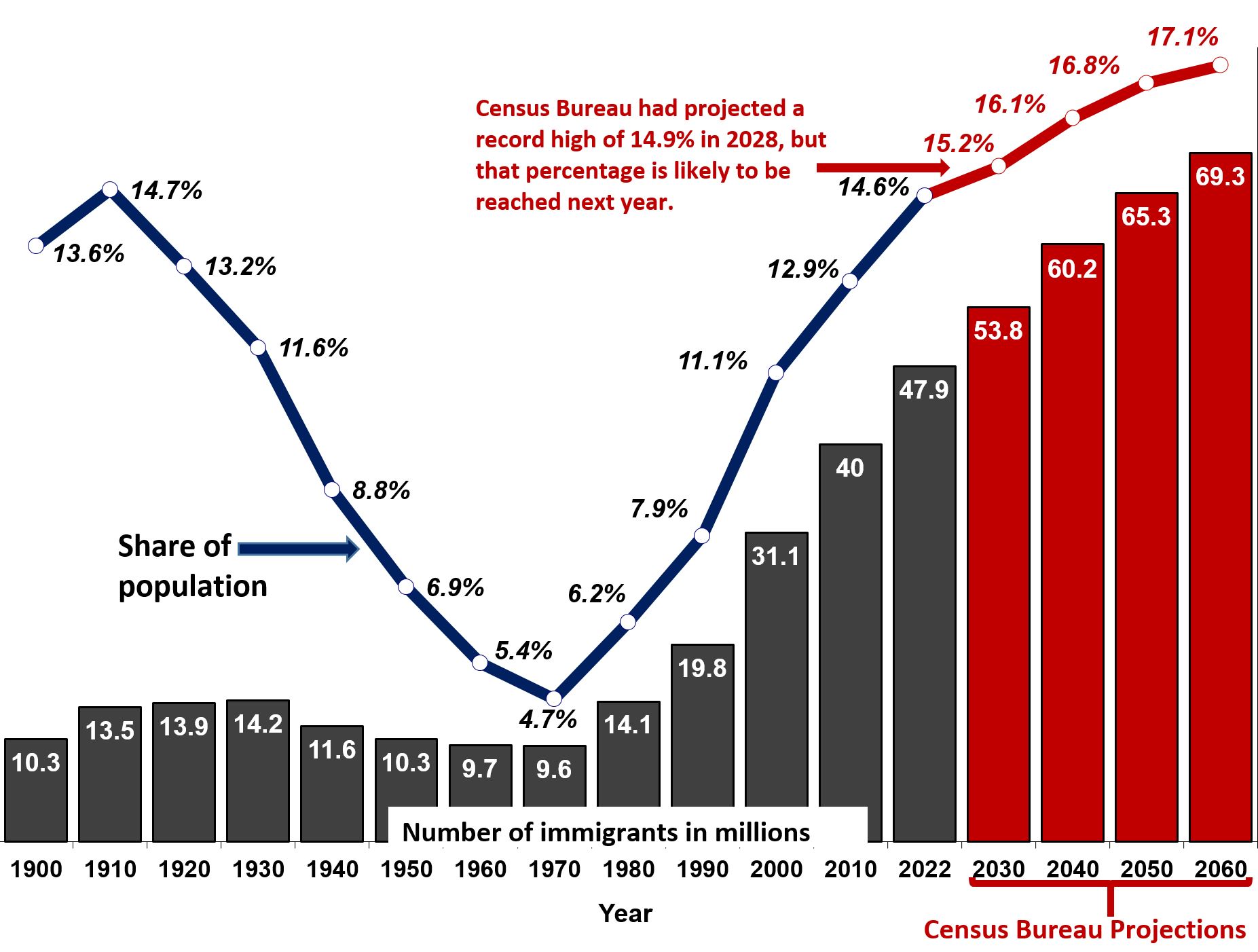

Traditionally, workers from developing countries, like India, would go to more affluent countries, such as the US or countries in Western Europe, looking for opportunities to utilise their skillsets and qualifications to the fullest potential and earn the highest rewards possible.

This started as a trend around the early 1960s and encompassed an array of professionals, including doctors, engineers, and information technology specialists. These workers had access to skills that were relatively scarce, and in great demand, at the time. As the years rolled on, students and workers in the fields of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics — collectively known as STEM — continued their exodus to richer countries. This STEM workforce was, and still is, much welcomed in all countries. It serves as the foundation for a thriving economy in an age wherein a country’s global status largely depends on its technological progress and prowess.

Over time, foreign-born populations have increased in developed countries, obtaining education and jobs internationally has become commonplace, and some developing countries, like India, are well on their way to equal, or in some cases surpass, their developed counterparts in the near future.

On the one hand, this has led to severe political divides in developed countries over social and economic issues ranging from jobs being taken away from domestic residents, to a perceived lack of cultural assimilation in society. On the other hand, despite having a resilient economy, India has been unable to fully capitalise on the outflow of talent and labour to further facilitate innovation and economic growth to improve job prospects and living standards for those who choose, or are compelled, to remain in their home country.

Thus, some course correction is warranted sooner rather than later.

Impact of Brain Drain in India

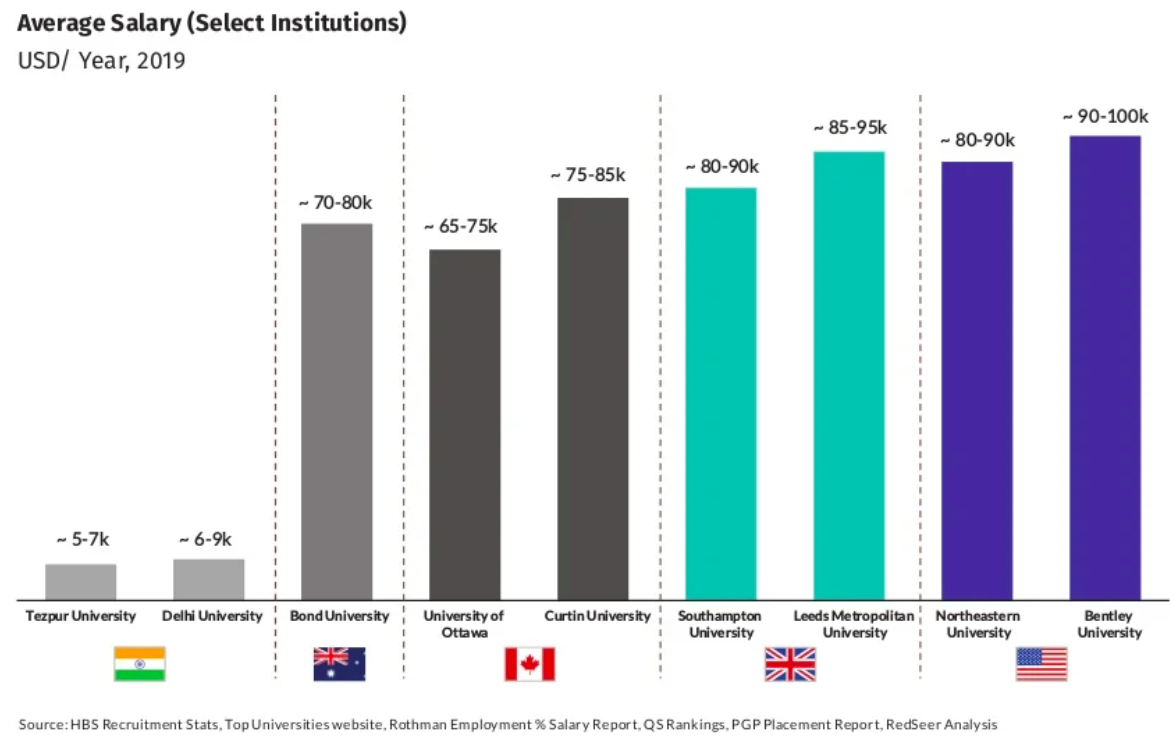

While there is no longer a severe dearth of business and employment opportunities in India as compared to the situation in the latter half of the previous century, millennials are still choosing to emigrate, but primarily for higher pay and quality of life (i.e., living standards, level of freedom in societies, better education systems, etc.). Consequently, the incessant pursuit of these two objectives is increasingly becoming the bane of young Indian workers’ existence.

In recent years, as skilled and educated people have been less likely to return to India, the country has depended on domestic entrepreneurs and workers to a greater extent. In response to the vacuum created by home-grown talent choosing to stay back in foreign countries, new Indian startups and domestic competitors to international corporations have opened up an avenue of opportunities for young workers.

However, the sheer size of the available workforce, the degree of competitiveness in the job market, and rising living costs in large cities have made basic well-being most coveted for a majority of the population. Moreover, the rising youth unemployment over the past three decades has virtually doubled.

Domestic booms in entrepreneurship help tackle the lack of job opportunities and curb unemployment to some extent. But the level of innovation required to launch the country into an ear-popping economic stratosphere can perhaps only be acquired if more of the best Indian minds choose to return and take advantage of all their country has to offer.

Indians who have either studied or worked in both their home country and developed economies abroad become ideal employers and employees in an increasingly globalised world, wherein it is crucial to stay in touch with one’s roots while also being aware of how to cater to foreign consumer markets. Developing soft skills by living and learning independently in an unfamiliar place complements the knowledge and abilities attained through a more traditional academic-oriented Indian institution or corporation perfectly.

In this way, the individual and the setting can be combined to amplify each other’s strengths. Although India’s population is not as young as it once was due to various reasons, including the global male infertility crisis, its workforce remains robust, geographic scope for different markets is immense, and untapped potential regarding innovation across sectors and industries is dumbfounding.

Additionally, notwithstanding temporary shortfalls in investment in its flourishing startup ecosystem, opportunities for businesses and ventures in most fields in India are riper than ever compared to those in more developed countries like the UK, Australia, or Canada.

Nevertheless, despite national grievances, and regardless of the attractive head starts that may be afforded to entrepreneurs in such a developing economy, it may take a while to harness and reverse the Indian brain drain for a myriad of reasons.

So, is Brain Drain Reversible?

Concerningly, young Indian graduates and freshers are not the only ones who view rich North American and European nations as preferable alternatives for settling down. Over the past few years, moneyed and relatively older citizens, who built their fortunes in India, are choosing to settle abroad, taking most of their wealth with them. Collectively, this mass migration of the most educated and wealthy Indians will prove immensely hard to reverse in the absence of acutely targeted policies based on rigorous research to incentivize the opposite.

Unfortunately, inertia due to a profitable status quo may prove a significant roadblock to implementing changes that imply a riskier and slower phase in regional and global economies.

As developing countries, like India and China, are catching up with their Western counterparts, there are fewer incentives for developed nations to stop talent poaching from other countries and instead focus on training their own populations in skillsets and educational degrees that have increasing relevance and usefulness as time passes. Developed economies will resist the reversal of brain drain through proactive efforts to sustain innovation and global leadership in vital sectors such as computer science, data analysis, financial management, and medical research.

Whereas India, which has been achieving an increased global economic footprint and the hard-earned respect of its peers internationally, may not be too eager to compromise this enhanced image perception and stronghold in the tech industry, among others, to gamble on the return of workers who left of their own accord, but continue to serve its grander interests, albeit unintentionally.

The host and home countries both have something to lose or risk in the uncertain short-run following an attempt at domesticating this unruly beast running amok. However, as countries now tend to focus more on internal issues and problems to veer away from self-destruction and stay afloat in this pool of globalised competition, there may still be light at the end of the drain.

The Path Forward

All countries have their strengths and weaknesses regarding the various sectors and industries in their respective economies. While an emphasis on the arts and social sciences may reflect the zeitgeist in some countries, others may be driven to prioritise technology or medicine. To an extent, the different cultural norms and expectations in Western and Eastern societies are also responsible for this.

Individual freedom in the creative pursuit of education and careers is essential. Nonetheless, governments must be wary and make efforts to leverage each other’s assets in ways that help avert large-scale or long-run economic slowdown for any population and hindrances to quicker short-term progress in any developing nation.

For example, this may be achieved by developed economies scaling down their dependence on foreign talent and prioritising incentivising their own students to pursue high-paying degrees by depoliticizing academic fields and raising awareness about majors that are currently leading to unpayable, crippling student debts. Developed economies exploiting the academic leanings of a country like India, while allowing political divides to infest their own academia, may cause disproportionate and unsustainable growth trends on both ends.

Cultural exchange programs and bilateral/multilateral conferences to orient, bolster, and develop the education and employment of people across borders could be another way of rebalancing brain scales tipping too heavily in any one direction.

In-depth discussion with my friend, India’s FM @DrSJaishankar on the strong 🇦🇹-🇮🇳 relations. Agreed to further boost economic cooperation & business ties, increase p2p-contacts & mobility whilst jointly combating illegal migration & human trafficking. India is a vital partner! pic.twitter.com/s5aXzeTzKi

— Alexander Schallenberg (@a_schallenberg) January 2, 2023

As for tasks that India must take upon itself in this regard, it should create attractive propositions to convince emigrants to return home after a suitable duration. The government should try to make it so that if an individual decides to settle in another country permanently, the individual’s decision should speak to the unique benefits the host country offers, as opposed to the embarrassing or avoidable drawbacks of staying in India.

Even though the government has attempted this approach through the Ramanujan Fellowship, VAIBHAV Summit, and Ramalingaswami Re-entry Fellowship, there remains much scope for efforts in this aspect.

India must expand its academic offerings, give its seemingly one-dimensional educational system a makeover, and facilitate women empowerment through education and career drives, in addition to subsidising the weaker sectors in its economy through focused government programs and foreign direct investments.

#IndiaAtUN

— India at UN, NY (@IndiaUNNewYork) March 9, 2023

🎥: Smt. Smriti Irani, Minister of @MinistryWCD delivers #India’s National Statement at #CSW67

"Reiterate commitment of 🇮🇳 to bridge the gaps by constantly striving to encourage women & girls to pursue a vibrant career in the digital & STEM fields..."

- @smritiirani pic.twitter.com/T72xPrltKH

Recently, there has been heartening progress of a kind regarding the former, with India moving to allow greater numbers of foreign universities to open up campuses on domestic soil.

Even if this helps to stem the talent outflow by a bit, it will afford policymakers some breathing room to dissect and address the other underlying motives of India’s brain drain to ensure it does not become a one-way street, but rather a boundless airspace in which ‘low’ or ‘high’ pressure is corrected for as a matter of course.