Over the last decade, female labour force participation for women in the child-bearing and child-rearing age has witnessed a worldwide increase due to reforms in family policies.

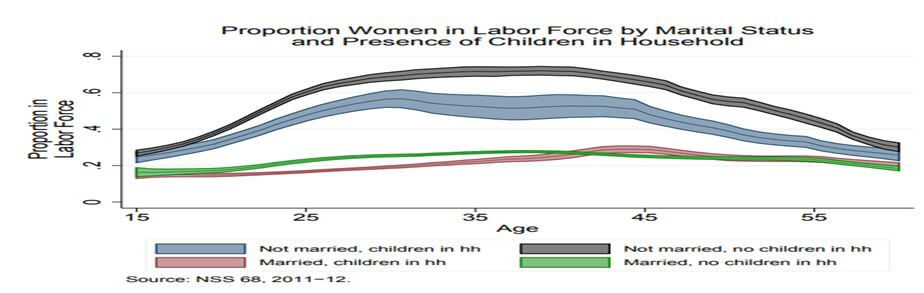

There has been a long-standing debate concerning the relationship between female labour force participation (FLFP) and fertility rates. Studies suggest that unmarried women are more likely to participate in the workforce compared to married women with young children. National Sample Survey Organization (NSSO) data also reveals a negative correlation between the number of young children in the household and women’s participation in the labour force. Women with children tend to prefer either temporary or part-time jobs or withdraw themselves entirely from the labour market. This is because women are more involved in the ‘care economy,’ which restricts their formal participation in the workforce.

The recent downward trend in India’s FLFP–from 36.7% in 2005 to 26% in 2018–poses a serious challenge and requires immediate policy intervention. Moreover, 95% of women are employed in informal or unpaid work. According to the study conducted by Associated Chambers of Commerce and Industry in India (ASSOCHAM), the majority of women exited employment after child-birth.

In response to these concerns, the Indian Government amended the Maternity Benefit Act, 2017. The amendment extends the paid maternity leave period from 12 weeks to 26 weeks for women working in the organized sector who have less than two surviving children. It also permits a 12 week leave for women adopting a child below the age of 3 months. Furthermore, it allows women to work from home after 26 weeks if their job profile permits, and has also made crèche facilities mandatory in the organizations with 50 or more employees.

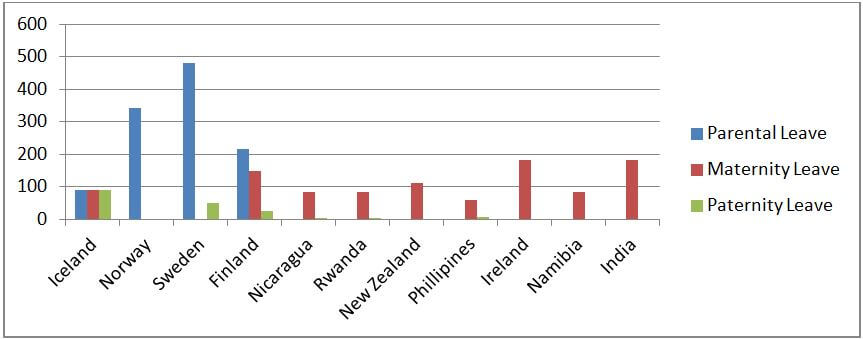

After amendments to the Maternity Benefits Act in 2017, India provides one of the most generous maternity benefits. The graph below compares the length of leave provided in the top 10 countries in the Global Index and India.

Despite these progressive measures, the Act still faces several challenges in terms of its coverage. For instance, it conflates childcare responsibility with maternity benefits, thus overlooking the male role in childcare. This reinforces a gender-based sexual division of labour. In 2017, Paternity Bill was proposed in the parliament. The private member bill proposed 3 months paternity leave across all the sectors. However, currently, only Central government employees are entitled to 15 days of paternity leave, and the bill is still under consideration.

Additionally, while India’s maternity leave is the third highest in the world, it covers only 1% of its women, as the law only covers women working in the formal and organized sector, thus excluding women working in the informal sector, which constitutes almost 93% of India’s workforce.

Moreover, the Act has made the employer entirely responsible for providing maternity benefits, thus shifting the entire financial burden onto the employer. This has made companies reluctant to hire women; as per reports, around 12 million women stand to lose their jobs due to the 2017 Act. The cost associated with the maternity benefits can strain micro, small and medium enterprises and start-ups, which account for around 40% of the workforce.

Conversely, countries like Australia and Canada offer fully state-funded maternity leave. Similarly, in Singapore, France and Brazil, the cost is shared between employers, the government, and social insurance schemes. Even in the countries compared in the graph above, only Rwanda, which is a low-income country, has employer-provided paid maternity leave. In other countries, the financial burden is borne by the government, social insurance schemes, or shared between the government and the employer. In fact, other than Namibia and Rwanda, all the countries have a provision of government-supported child care and child allowances.

Alongside a lack of government-funded or supported maternity benefits, there are also currently no paternity leave provisions outside of central government employees. As per 2015 International Labor Organization (ILO) data, paternity leave provisions are provided in 90 out of 170 countries. For instance, Iceland has the criteria of 3-3-3, in which it provides 3 months of leave to both mothers and fathers and another 3 months to be shared between the two of them. Through the scheme, Iceland focuses on child development and has also reduced the gender wage gap after the implementation of the Act, and ranks first for gender pay parity in a study by the World Economic Forum.

Norway has implemented similar institutional interventions to achieve gender parity in the workforce. For example, it provides fully state-funded parental leaves in order to enabled shared childcare and household responsibilities, offers a 'caring allowance' that guarantees employees paid leave when their child is sick, flexible working hours, and well-structured kindergarten and after-school programs. This has significantly impacted women’s labour force participation in the country. The FLFP has risen from 44% in the 1970s to 76% in 2012, and 83% of mothers with young children are now employed. This has led to a growth of 20% in the nation's GDP per capita over the last 40 years.

While it is vital to highlight the key successes of these policies, it is not merely the specifics of these policies, but also the general prioritization and promotion of, and responsiveness to, the unique gendered issues within their country's politics and society that has contributed an increased FLFP. Systematic efforts of sharing childcare and household responsibilities, early childhood care and welfare family and gendered based policies have created an inclusive economic society.

Currently, India ranks 120th among 131 countries on FLFP, as per World Bank’s 2017 India Development Report. According to a study by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), India can boost its GDP by 27% if it raises its FLFP at par with men.

For India to achieve similar results to Norway or Iceland, and address the limitations of the Maternity Benefit (Amendment) Act, it must tackle the unique challenges facing women in the country. In order to create a rise in FLFP, it is imperative to create a maternity policy that is not only funded in part, or wholly, by the state, but also one that covers workers in both the formal and informal sectors. Likewise, provisions for expanding child care services such as pre-primary education, child care centres and extended school hours are equally important in facilitating FLFP. Lastly, and most importantly, parental leave arrangements should be updated to share the childcare responsibility between both the parents in order to reduce the existing sexual division of labour.

Considering that majority of women work in the informal sector and withdraw or remain absent from the labour force due to the sexual division of labour and discriminatory practices, maternity benefits are essential to provide income security, promote health and well-being of mothers and children, advance safe and decent working conditions, and achieve gender parity in the workplace. Female Labor Force Participation is an essential prerequisite in developing an inclusive and sustainable economic structure.